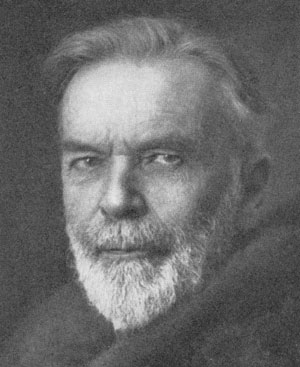

[p.IX] Wilhelm Geiger

WILHELM GEIGER; July 21, 1856—September 2, 1943

WILHELM GEIGER; July 21, 1856—September 2, 1943

Wilhelm Geiger was a scholar who covered an unusually wide field of research and who, as a pioneer, opened up new ways and fields of study. Therefore, his lifework cannot be described simply in terms of Pāli philology. We have to recognize three main parts of at least equal importance in his work: his Iranian studies, his Pāli studies, and his studies of Ceylon and the Sinhalese language. In this dictionary, however, we can deal only with his Pāli studies, and especially with his contribution to Pāli lexicography. To a certain extent, though, his studies of Ceylonese history cannot be separated strictly from his work on Pāli, because the earlier Ceylonese chronicles have been handed down to us in the Pāli language.

Geiger, who was born in Nuremberg in 1856, studied Oriental languages under Friedrich von Spiegel at the University of Erlangen. Spiegel was (after the Norwegian-born Christian Lassen) the first German Pāli scholar and the first German scholar to edit Pāli texts ("Kammavākya, liber de officiis sacerdotum Buddhicorum", 1841; "Anecdota Pālica", 1845) and to collect materials systematically for a dictionary of Pāli. The manuscript of this dictionary ("Lexicon Pālicum", 2 vols., 282 and 260 pp.) was never published. Later, Spiegel turned to Iranian philology and never returned to Pāli philology. When Geiger studied under him, he had already put aside his Pāli studies.

Geiger took the degree of Dr. phil. with a thesis on an Avestan text ("Die Pehlevi-version des Ersten Capitels des Vendīdād") in 1877. Shortly afterwards he published a study in the field of Western Classics: "De Callini elegiarum scriptoris aetate" (1878). [p. X] It is still referred to in modern handbooks of Greek literature. But soon he concentrated on Oriental studies again and became lecturer (Privatdozent) in Erlangen after he had presented his edition of the Aogemadaēcā (1878) as his "Habilitationsschrift". Although Geiger was forced to earn a livelihood as a teacher of Latin and Greek at the Gymnasium at Neustadt an der Haardt from 1880 to 1884, far away from any large libraries, he published a series of very important studies mostly of Iranian languages, literature, and history. In 1884, Geiger was appointed teacher at the Maximilians-Gymnasium in Munich, besides which he was also a lecturer at the University of Munich from 1886. During this time he won the intimate friendship of Ernst Kuhn and of Mark Aurel Stein (later Sir Aurel Stein).

Although Geiger continued his work on Iranian subjects for some years after he had become Professor of Comparative Philology at the University of Erlangen in 1891, as the successor of Spiegel, he now began to develop an interest in Pāli and Sinhalese. He himself has described this turning point in an unpublished autobiographical manuscript with the following words:

"Die Übersiedlung nach Erlangen bedeutete zugleich meinen Übergang von der Iranistik zur Indologie. Wie ich auf iranischem Sprachgebiet vom Altertum (Awesta) bis zur modernen Zeit mich durchgearbeitet hatte, so wollte ich nun einen ähnlichen Weg auf indischem Gebiete gehen . . .

Meine indologischen Studien nahmen von Anfang an die Richtung auf das Singhalesische. Das kam so. In Erlangen studierte bei mir zu Anfang der 90er Jahre ein junger Singhalese, Don Martino de Zilva Wickremasinghe. Er . . . machte sich (später) um die Inschriftenkunde wirklich verdient . . . Es versteht sich, daβ wir oft zusammen über seine Muttersprache und ihren damals noch nicht so recht aufgeklärten linguistischen Charakter uns unterhielten. Während ich mich nun zunächst in das Pāli, die heilige Sprache des in Ceylon noch lebendigen Buddhismus, einarbeitete, wurde in mir der Wunsch lebendig, selber nach Ceylon zu reisen und die singhalesische Sprache an Ort und Stelle zu studieren. Ich konnte ja hoffen, damit zugleich meine alte Sehnsucht, fremde Länder und Völker, insbesondere die Tropennatur kennen zu lernen, aufs beste zu befriedigen."

On November 18th, 1895, Geiger started on his first journey to Ceylon which he vividly described in his book "Ceylon, Tagebuchblätter und Reiseerinnerungen" (1898). Shortly after his arrival in Colombo, in answering the questions of a Ceylonese journalist in Colombo about the purpose of his visit, he said (according to an article "Professor W. Geiger in Colombo" published in a Ceylon newspaper):

"I have been sent ... to study Sinhalese, especially for scientific purposes. I hope to find out whether it comes under the category of Aryan languages or not. That is still a subject of dispute among leading men in Europe, and I have come to see if I can settle that bone of contention."

And he could. In 1897 he published a treatise on the language of the Roḍiyās in Ceylon, in 1898 the first (German) edition of his etymological glossary of the Sinhalese [p. XI] language, and in 1900 his "Litteratur und Sprache der Singhalesen". He himself wrote of the importance of his journey:

"Daβ die Reise mir auβerordentlich viel bedeutete, versteht sich von selbst; sie wurde aber geradezu entscheidend für mein ganzes weiteres wissenschaftliches Leben. Ceylon ist meine Arbeitsdomäne geworden . . ."

Again, his studies of Ceylon led him to an intensive study of Pāli. We may refer here to his own words once more:

"Aber Ceylon hatte es mir nun angetan, nicht nur seine Sprache, sondern auch seine Geschichte und seine Kultur. So versteht es sich, daβ ich in die Pālisprache mich besonders vertiefte . . . und in den Mahāvaṃsa, die [damals] in recht unvollkommener Ausgabe und Übersetzung vorliegende Chronik der Insel. Ich habe sie denn auch in je 3 Bänden neu ediert und übersetzt. Die englische Regierung in Ceylon hat dieses Werk finanziell unterstützt und mir auch im Jahre 1925/6 eine groβe [zweite] Reise nach Ceylon und durch die verschiedensten Teile der Insel ermöglicht, auf der ich die notwendige lebendige Anschauung der Schauplätze mir aneignen konnte, wo die verschiedenen geschichtlichen Begebenheiten sich abspielten.''

Geiger's edition and translation of the "Great Chronicle" (Mahāvaṃsa), a masterpiece of critical philology, was published between 1908 and 1930. Further he contributed to our knowledge of Pāli literature by investigations into the sources and development of the Pāli chronicles in his book "Dīpavaṃsa und Mahāvaṃsa und die geschichtliche Überlieferung in Ceylon", 1905 (English translation by Ethel M. Coomaraswamy: "The Dīpavaṃsa and Mahāvaṃsa and their historical development in Ceylon", Colombo 1908), and also in a number of papers ("Noch einmal Dīpavaṃsa und Mahāvaṃsa", ZDMG 63 p. 540ff.; "Die Quellen des Mahāvaṃsa", ZII 7 p. 259ff.; "The Trustworthiness of the Mahāvaṃsa", IHQ 6 p. 205 ff., etc.).

When Geiger was already reputed to be one of the most eminent Pāli scholars, two tasks fell to him: first, to lend his assistance to the plan of an international Pāli dictionary and, secondly, to write a grammar of Pāli.

"The Pāli Text Society's Pāli-English Dictionary" by T. W. Rhys Davids and William Stede was to a certain extent the result of the abandonment of the plan for an international Pāli dictionary. Such has been hinted at in the foreword to that dictionary (p. VII) and in the preface to "A Critical Pāli Dictionary" (Vol. I, p. IX f.). Wilhelm Geiger was requested as early as 1903 to co-operate in the work on the dictionary. According to the plan as published by T. W. Rhys Davids in the Report of the Pāli Text Society for 1909, Geiger, with M. Bode as co-worker, was to become the author of volume III comprising the letters P-M. Geiger had later extended his collection of lexicographical materials, originally a list of words from the Pāli chronicles, and he started to collect words and references from various other texts, especially from some parts of the Vinaya, parts of the four Nikāyas, Dhammapada, Udāna, Suttanipāta, Jātaka with its commentary (especially vols. I and III), Dhammapadaṭṭhakathā (I.1 and III), Dāṭhavaṃsa, Hatthagallavihāravaṃsa, Rasavāhinī, etc. Soon he realized [p. XII] that it was useful not to restrict his collection to the labials only, but to collect materials for the whole of the alphabet.

In 1916 Ernst Kuhn, who was appointed author of volume I after the death of Edmund Hardy, wanted to retire from this job and asked Geiger to take over this part of the task, too. Kuhn wrote to Geiger in a letter dated January 30th, 1916:

"Um nun nicht den Vorwurf auf mich zu laden, daβ ich bis zu meinem Tode die Genossen in Buddha an der Nase herumgeführt habe, bin ich entschlossen, das gesamte bei mir befindliche Material vertrauensvoll in Ihre Hände zu legen mit der herzlichen Bitte, an meiner Stelle die Bearbeitung zu übernehmen. Es sind dies zunächst Hardy's Sammlungen zu den Vocalen mit ergänzenden Aufzeichnungen des Ehepaares Rhys Davids und Hardy's wie Pischel's Exemplare des Childers mit wertvollen handschriftlichen Nachträgen......Die von mir begonnene Arbeit an den Artikeln a bis akhaṇḍa behalte ich einstweilen zurück, um sie lesbar abzuschreiben und dann Ihnen gleichfalls zuzustellen."

Geiger agreed and accordingly intensified the collection of materials for the dictionary. Communications between the scholars of different nations being cut off by the First World War, he could not know, of course, that the plan for an international Pāli dictionary was already out of date. In Copenhagen, at the same time, Dines Andersen (who had been appointed author of volume IV of the planned international dictionary) and Helmer Smith conceived a plan of editing a Pāli dictionary based on the materials left by V. Trenckner without the aid of foreign collaborators. Thus they started "A Critical Pāli Dictionary" (see CPD, vol. I p. X). Independently T. W. Rhys Davids decided to supply a provisional dictionary to be written as fast as possible in England and to be edited by the Pāli Text Society, a task performed with the help of William Stede in 1921—1925.

In this situation Kuhn and Geiger in October 1919 decided to aid the progress of the Pāli Text Society's dictionary by sending all the materials that had come into their hands (as specified in Kuhn's letter reproduced above), including Kuhn's Pāli collections, to T. W. Rhys Davids. Furthermore, they asked the Bavarian Academy to pay the amount set aside from the "Hardy-Stiftung" for the Pāli Dictionary to the Pāli Text Society (see also PED, Foreword p. VIII). Geiger's own collections, however, remained with him, and he continued enlarging them. After Geiger's death Helmuth von Glasenapp was the first to mention Geiger's "umfangreiche Zettelsammlungen, die ein gewaltiges Wortmaterial umfaβten", in his obituary in ZDMG 98 p. 183. Mrs. Magdalene Geiger entrusted Helmut Humbach and the writer to take care of these collections. I may refer readers to the Preface to Volume II of "A Critical Pāli Dictionary" p. III for the agreement of January, 1960, with the Royal Danish Academy that led to the inclusion of Geiger's collections in the CPD from Volume II. Geiger's work now can serve the purpose for which it was originally intended: to help in the preparation of a Pāli dictionary by international collaboration of scholars. It might be mentioned here that Geiger's Pāli Dictionary is written on paper slips measuring 10.4 x 8.5 cm. For each reference the meaning of the word is stated.

[p. XIII] Although Geiger's Pāli Dictionary was to become useful for the public only many years after his death, his grammar of Pāli has been an indispensable book since 1916 for every Pāli scholar. This book, too, has a somewhat remarkable history. Originally it was Richard Otto Franke who was invited in 1893 to write a grammar of Pāli as part of the "Grundriβ der Indo-Arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde" ("Encyclopedia of Indo-Aryan Research"). In 1902 Franke started to publish studies of some special problems of Pāli philology ("Geschichte und Kritik der einheimischen Pāli-Grammatik und -Lexikographie"; "Pāli und Sanskrit") and to prepare concordances to the verses of several Pāli texts, but the completion of the grammar was delayed longer and longer. A grammar of Pāli, however, was urgently needed at once then. After Franke had given up the task, Jacob Wackernagel as the editor of the first part of the "Grundriβ" entreated Geiger to write the grammar immediately. Geiger did not refuse to help, and in 1916 his "Pāli, Literatur und Sprache" was printed.

It has later become a standard work. Its translation into English by Ratakrishna Ghosh (including some important additions by Geiger himself) was published by the University of Calcutta in 1943 and reprinted in 1956. The collections gathered by Geiger for the dictionary were, of course, a valuable help for the fulfilment of the difficult task of writing the first (and till this day the only) comprehensive grammar of Pāli based on the study of texts. I need not repeat recommendations of it by scholars like Helmer Smith and Franklin Edgerton reproduced in another place (Editor's Introduction to Geiger, Culture of Ceylon p. XV f.), but I may mention here that recent grammars of Pāli have not been able to add any important new materials from Pāli texts to those reproduced from Geiger's book. Not less remarkable than the completeness of his grammar is the transparency of the arrangement and the clearness of the expression and of the formulation of the rules found by him. The limitation of size for this volume of the "Grundriβ" prevented him from including an examination of the syntax, but he left an unpublished manuscript with collections for a syntax of Pāli ("Sammlungen zur Syntax des Pāli").

In 1918 Geiger, jointly with his wife Magdalene Geiger, edited and translated the second section of the famous collection of stories called Rasavāhinī ("Die zweite Dekade der Rasavāhinī"), the first section of which had already been published by Spiegel in "Anecdota Pālica" (1845). In 1920 Magdalene and Wilhelm Geiger published a treatise on the meaning of the word dhamma which has become one of the indispensable handbooks of Pāli philology ("Pāli Dhamma vornehmlich in der kanonischen Literatur"). An important addendum to this work is his study "Dhamma und Brahman" (1921), and for some years he continued the series of Pāli studies culminating in a translation of Volumes I and II of Saṃyutta-Nikāya ("Saṃyutta-Nikāya, die in Gruppen geordnete Sammlung aus dem Pāli-Kanon der Buddhisten zum ersten Male ins Deutsche übertragen", Vol. I, 1930; Vol. II, 1925). He succeeded in presenting a translation remarkable both for the utmost preciseness and for the beauty of the language employed.

In the meantime Geiger was invited to succeed Kuhn in the chair of Indology and Iranian studies at the University of Munich in 1920. A few years later, after he had passed [p. XIV] the age of 68, he retired from his chair and spent the rest of his life in the small village of Neubiberg near Munich. Many honours were conferred upon him during these years: in 1926 he was appointed Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy, in 1929 Honorary Member of the American Oriental Society, in 1930 Honorary Member of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, in 1934 Honorary Member of the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft, in 1935 Honorary Member of the Société Asiatique in Paris, and in the same year Honorary Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Even as far as Japan, his name was celebrated now: in 1934 a Japanese medal in memory of the 2500th anniversary of the Buddha's birthday was conferred on him as one of only seven scholars in the field of Buddhist studies who were deemed to deserve this honour.

And there was no interruption of his prolific work after his retirement. But during the last 15 years of his life Geiger concentrated more and more on studies of Ceylon, and therefore he no longer published works on Pāli philology in the strict sense of the word. His notes about the interpretation of difficult passages in the Pāli canon and about the development of the Buddhist doctrine in the canonical books remained unpublished. One of Geiger's letters written in Pāli to A. P. Buddhadatta Mahāthera, however, has been published by this Sinhalese scholar (A. P. Buddhadatta, Śrī-Buddhadatta-caritaya, Colombo 1954, p. 147 f.) and since then, it figures as a part of the standard materials in Ceylonese school books on Pāli (e.g. A. P. Buddhadatta, Aids to Pāli Conversation and Translation, Ambalangoda s.d. p. 130f.).

But even in his Ceylonese studies Geiger did not lose contact with Pāli philology. First, he completed the redaction and translation of the Mahāvaṃsa, the first part of which had already appeared in 1908, as mentioned above. In order to help this undertaking, the Government of Ceylon invited him to visit the island in 1925/6. And after he had agreed to become director of the "Dictionary of the Sinhalese Language" in Colombo he went to Ceylon in 1931/2 for a third time. In this task he closely collaborated with Helmer Smith, who, invited by Geiger, joined as a director of that dictionary in 1936. After the completion of "A Grammar of the Sinhalese Language" (1938) and other important contributions to Sinhalese philology, he again concentrated on a study of the Mahāvaṃsa, but now for an entirely new purpose, namely to investigate mediaeval Sinhalese culture. When he had succeeded in completing the manuscript of "Culture of Ceylon in Mediaeval Times" in 1940 (published in 1960) and in providing an examination of the Sinhalese syntax in "Studien zur Geschichte und Sprache Ceylons" and "Beiträge zur singhalesischen Sprachgeschichte" (1942), he had achieved the rounding-off of his lifework, as it had been his aim from his youth.

Heinz Bechert.

A Critical Pāli Dictionary Online is maintained by the Data Center for the Humanities at the University of Cologne in cooperation with the Pali Text Society. The project was originally carried out by the Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies (ToRS) at the University of Copenhagen. It has been set up again in 2016 by Marcello Perathoner (Cologne Center for eHumanities) • Contact: cpd-contact@uni-koeln.de • Data Privacy Statement (German)